Grafton plastic alto saxophone

Origin:

UK Origin:

UK

Guide price: Variable, heavily dependent on condition

Weight: Not much at all

Date of manufacture: 1950's - 60's

Date reviewed: November 2005

The world's first synthetic-bodied saxophone,

and arguably an icon of the 20th century

There aren't many instruments that strike fear into the heart of

the woodwind repairer, but the Grafton alto is definitely one of

them.

I reckon a repairer averages three overhauls on these creatures;

the first out of ignorance and sheer curiosity; the second out of

disbelief that any instrument can be such a pig to repair and the

third just to be really sure that the thing really exists and isn't

just a terrible nightmare. The truly masochistic (or perhaps forgetful)

might tackle four.

The thing that makes and (quite literally) breaks this horn is

the synthetic body.

Although often referred to as the Grafton Plastic Alto, it's in

fact made from an acrylic plastic - and it's just about the most

brittle plastic ever made. What's worse is that it's extremely difficult

to repair - very little seems to want to stick to it.

This, essentially, is the reason these horns are so rare - they

simply fall apart unless handled with the greatest of care, and

to find one with no cracks or splits on it is getting to be near

enough impossible these days.

Naturally, this built-in obsolescence has turned the Grafton from

a 'chuckaway' horn that you could have picked up for about fifty

quid in the 70's to an icon of 50's design that regularly fetches

four figures (or rather much more in one significant case).

And iconic it certainly is. No less a giant that Charlie Parker

played on one, as did Ornette Coleman. Glam rock fans might well

recall a certain Mr. Andy Mackay playing one with Roxy Music - and

it was Parker's Grafton that sold at auction a while back for a

few grand short of £100,000. They do say that on the very

quietest nights you can hear the soft, dull thud of one-time Grafton

owners kicking their own backsides for selling their horns for the

price of a night out in town all those years ago.

Of course, it's doubtful that any of these people played one because

of its tone or response - the one thing the Grafton has that no

other sax has ever had is that unmistakable look.

That it looks as good as it does is probably down to the fact that

the designer, Hector Sommaruga, was an Italian by birth.

Just look at the bell key guards...they simply ooze Italian '50s

style.

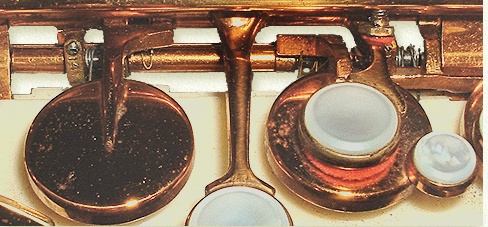

Up close and personal, things are rather less rosy for the Grafton.

Whilst the design of the action is a tour-de-force in terms of

overcoming the constraints of working with a synthetic body, the

end result is rather disappointing in terms of feel. Without being

able to use traditional needle springs, the designer resorted to

using coiled springs - exactly like those you'd see on baritone

sax and brass instrument water keys.

For

sure, they work well enough, but they don't have an ounce of 'snap'

to them, which lends the Grafton a typically spongy feel. For

sure, they work well enough, but they don't have an ounce of 'snap'

to them, which lends the Grafton a typically spongy feel.

They're also one of the reason these horns are such a pig to repair

- as soon as you withdraw the stack rod screws, these springs ping

off in all directions, and they're the very devil to put back on.

They're not exactly stock items these days either, so any lost or

broken springs have to be made from scratch.

It's actually not as hard as it sounds, and I believe I still have

a tool knocking about the workshop which I built to knock up water

key springs from phosphor bronze wire back in my college days.

Note the 'balanced action' type adjustment screw above the A key

touchpiece.

Another huge drawback was the impossibility of bending keys on

the horn.

Oh sure - you could bend the keys (as you would do when adjusting

key angles etc.) but your efforts would be repaid with a sickening

crack as the key mounting stub cracked off from the body.

This particular feature presents the owner with something of a paradox

- if you want to have one of these things repaired you'd be seriously

well advised to find a repairer who's tackled one in the past, unless

you want your horn back with assorted stubs cracked off it...but

if you find such a person there's a very good chance they'll refuse

outright to work on the thing - and if they do consent to work on

it you can expect to pay a very considerable premium. I'll just

say that again...a very considerable premium. Mmmm.

By far and away the most common problem with Graftons is the flimsiness

of the key guards, their mounting stubs and the bell brace. The

whole point of key guards is to absorb the casual knocks and dings

that every sax is subjected to in normal use, but the Grafton isn't

built to take such punishment. You really wouldn't believe just

how light a knock it takes to crack the guards and knock off the

mounting stubs. This particular horn is the very first one I've

ever seen that's had intact guards and stubs.

It's also the first I've seen that doesn't have a glued-up bell

brace.

As

you can see, it's a very insubstantial affair - and it's been said

that you can break this brace simply by swinging the horn a little

over-enthusiastically during a solo. Even dropping the horn into

it's case with undue care can see off this joint. As

you can see, it's a very insubstantial affair - and it's been said

that you can break this brace simply by swinging the horn a little

over-enthusiastically during a solo. Even dropping the horn into

it's case with undue care can see off this joint.

This particular shot shows up the integral tone holes quite well.

The pads as fitted were atrocious. It's interesting to note that

the vast majority of Graftons still have their original pads fitted...simply

because very few people are brave enough to attempt replacing them.

Consequently most Graftons are plagued with spongy, leaky pads.

It's a shame really, because the design of the integral tone holes

is a good one, and despite the somewhat vague and slightly loose

keywork, the pad cups are generally quite flat.

If you wanted to replace the pads I'd advise a very soft pad with

a fairly soft skin - a soft MusicMedic's

'roo skin' pad would fit the bill admirably.

Under the fingers the keys all seem to fit in the right places.

Ergonomics were never really an issue with the horn - but the inherent

play in the action, coupled with the coiled springs and the dodgy

pads makes the whole action feel somewhat hit and miss. This makes

playing the horn a rather trepidatious affair - you feel as though

you want to clamp your fingers down hard in order to seal the pads,

but you daren't put too much pressure on the keywork in case you

bust a stub off.

One major criticism of the Grafton has always been the tone it

produces - or so people would have you believe.

This particular horn was brought in by Pete

Thomas, who first instructed me to close my eyes while he blew

the as yet unseen sax.

He blew, and I listened, and my initial thoughts were that, tonewise,

the sound was quite 'bootsy' but with a little something missing

in the midrange, though not overly bright up top nor boomy down

low. My first guess was a cheap Chinese horn - it had that sort

of sound...good, but not polished. My second guess was a Conn 6m...there

was a fair bit of warmth to the tone, and quite a bit of power..the

sort of tone you'd get from a 6M with a vintage mouthpiece perhaps.

You can imagine how surprised I was to open my eyes and find the

Grafton alto!

When I blew it it put me in mind of a vintage midrange horn. The

tone wasn't unpleasant, and yet it lacked the sparkle and zing that

you'd get from a pro quality horn - and about the best analogy I

could come up with was that it sounded like an ordinary sax being

played behind a thin felt wall...slightly furry at the edges, as

Pete succinctly put it.

I've heard it said that you can't play a Grafton alongside another

sax player because of the difference in tone.

Complete rubbish. I've sat beside many a decent player who's had

a far more woolier tone than the Grafton puts out, including one

lovely old gent whose alto tone sounded like Ben Webster playing

under a duvet - which is quite a feat, when you think about it.

My Rousseau mouthpiece lifted the clarity a little, and a brighter

piece would introduce the requisite sparkle if you so desired.

So why did these strange beast die out?

Well, as mentioned, the chief reason was their fragility, unreliability

and difficulty when it came to repairs - but perhaps the biggest

impact came from sheer prejudice.

You have to remember that this horn was cutting edge in its day,

and if I've learnt one thing in my decades of being surrounded by

musicians it's that they can be a remarkably conservative bunch

when it comes to innovations in design. The exact same thing happened

with the introduction of mass-produced horns from Japan in the 1970's

- and you'll still find many a modern-day clarinettists who pours

scorn on 'plastic' clarinets. Witness too the resistance to adequate

Ultra-Cheap horns coming out of China these days.

What really must be remembered is that this horn was never intended

to be used as a professional instrument. The whole point about it

was that it could be built cheaply and easily, and thus sold cheaply

to beginners. In other words it's the Buffet B12 of saxophones -

and that's something that has to be taken into account when assessing

its action and tone. That it found its way into the professional

'hall of fame' is perhaps more than the designer could ever have

hoped for.

I still believe the premise was a sound one, and it's perhaps an

idea that's well overdue for a fresh look. There are many advantages

to using a synthetic body, and pretty much all of the disadvantages

that plagued the Grafton could be easily overcome with modern plastics

and resins.

Just think of it...a carbon-fibre horn, fitted with L.E.Ds moulded

into the body that light up as you play! Who could resist it?

At the time of writing this review (2005) the Grafton was unique

in having a synthetic body, but since then we've seen the debut

of the Vibratosax - which takes the concept a step further by also

using synthetic materials for the keywork. I think it's fair to

say that, like the Grafton, it has its problems.

Mr Sommaruga certainly left a legacy behind him. Even today, the

Grafton never fails to impress whenever it makes its appearance

on stage - and it impresses in two distinct ways. For the punters,

it's simply down to the art-deco looks...but for any watching saxophonists

it's more likely to be because the thing hasn't yet fallen to pieces.

Much as I hate to say it, it's not really a player's piece anymore.

Its rarity and fragility have turned it into an 'investment opportunity',

and one that's likely to increase in value year on year. I expect

we'll still see them popping up on major gigs for the next few decades

- and the simple glamour of the horn will mean that there'll always

be a market for a Grafton that actually works.

For a more in-depth look at the technical issues surrounding an

overhaul of one of these horns, check out my article on The

Naked Grafton.

|